Post-webinar chat with myself

I am a ‘boomer’ so I still make New Year’s resolutions (well, sort of). This year I decided that I will take better records of my engagements in various online events so that I am able to share some of my thoughts through the ARTNeT E-forum which was created for more informal sharing of ideas linked to sustainable development and trade.

Yesterday, I was invited to be a panellist in the session on Sustainable Trade organized by the MCB Trade Law Program and the Centre for a Smart Future, Sri Lanka along two other panellists Daniel Ramos of the WTO and Dilhan C. Fernardo, Dilhan Conservation. Anushka Wijesinha, CSF provided excellent closing remarks. The online webinar was very well organized and run but as in many other occasions, there was not enough time to address all issues or provide additional comments, evidence and sources of data. So, I am recreating questions I was asked by the moderator Sandun Batagoda, MCB and providing my comments to share in this forum.

1. What are some of the key aspects of sustainable trade in the Asia Pacific region, and, has there been much activity on this front through Regional Trade Agreements?

When thinking of sustainable trade from the Asia-Pacific perspective, I must point out that the Asia Pacific space is so vast encompassing many countries at various levels of development, different natural resource endowments and different pollution absorption, among other differentiating factors. Thus, there could be no single position on this subject. It has all the complexity of the global discussions with one added -and a very important- factor. Trade has been the key driver of growth in the most economies in the region, there is extensive evidence about trade being the force for reducing poverty in Asia-Pacific. While this steam of the trade as an engine of growth has lost its peak strength it had at the time of hyperglobalization peak around 2008, trade remains important determinant of prosperity in the region. This role of trade has been recognized by tying trade to the key means of implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. This linkage must be considered when thinking about sustainable trade that is fit for the region.

We distil the concept of sustainable trade from the grand notion of sustainable development keeping all three of its dimensions. Thus, sustainable trade means participating in the international trading system in a manner that supports the long-term domestic and global goals of economic growth, environmental protection, and strengthening social capital. Some will recognize this definition from the Sustainable Trade Index reports.

The biggest mistake when thinking about sustainable trade is to see it through the prism of transportation. Trade is much more than just moving goods from A to B. Trade involves decisions on how to use resources in a production process and post consumption management. So thinking about sustainable trade simplistically by replacing it with “buy local” will reduce some GHG emissions related to transport (10% of GHG emissions in Asia Pacific region) but replacing them by local production may often add more emissions as local production may be much less clean – as documented in the latest APTIR 2021.

These arguments asking to substitute or even eliminate trade are linked to the arguments about a trade-off between economic growth and clean environment or now in the pandemic times arguments between efficiency and resilience. It would be wonderful if one could swap unit by unit one for another. It does not work that way – as documented in the mentioned report and other literature and public needs to be better informed about the real choices.

Another reason we cannot think in terms of trade-offs only is that often pushes aside – out of the picture – the inclusivity aspect of sustainable trade. We are accustomed to look through 2 dimensions (growth-emissions, for example), but we need to add social impact of that equation.

So, unless sustainable trade delivers prosperity, fairness in distribution and environmental responsibility to the region it will not be sustained, nor it can be a driver of resilience.

What do we need to put in place to have sustainable trade? We need policy incentives to change behaviour of economic actors. For this, we cannot rely only on trade policy- we need a host of measures with wider and longer reach than trade policy itself. We should start with policies that can easily correct negative externalities (production and consumption taxes but also reviews of tariff structure). Trade policies have been so easily used to promote narrow political economy agendas (that is, vested interests)- we need to learn to use it to promote a different political economy agenda of (improved) social and environmental responsibility. “Trade for all” has become a trade strategy to go to.

Further, we should not shy from using trade policy (and complementary policies) in support of positive externalities, so to encourage their creation. Subsidies come to mind, of course, not those bad or harmful subsidies (for instance fossil fuel subsidies, agriculture, fisheries) – instead, we need to promote technologies, R&D, education to allow us to transform economies to be smarter and cleaner.

(APTIR 2021 provides rich evidence on the impact of such policy incentives- I cannot go into details here so I invite all to read this recently published ESCAP-UNEP-UNCTAD report.)

You asked me also about regional trade agreements (RTAs). Very briefly, the RTAs are favourite modality of many Asia-Pacific policymakers when thinking about trade and investment strategies. RTAs served a purpose of filling in the policy instrument gap which occurred due to issues with the multilateral system and lesser willingness to undertake unilateral reforms (this later, I guess, occurring due to a lesser pressure from the international organizations such as the IMF to align with the mainstream economic structure and because of the stronger internal political economy pressures to deliver quid-pro-quo trade results). However, RTAs have been slow to discipline provisions promoting sustainability. The older trade agreements (e.g., those put in place prior 2010) were mostly concerned with opening partners’ markets and attempting to control unfair competition (for instance, by focusing on dumping, state enterprises, labour and environmental standards). Trade agreements negotiated more recently – often called partnership agreements – tend to have added aspirations of cooperation for development and thus their potential to deliver on promoting sustainable trade (and development) is stronger. The range of instruments that could be effectively used through such agreements are of course tariffs and non-tariff barriers (by aiming to relax those on environmental goods and services); mutual recognition of standards to ease recognition of international standards; enhancing transparency and hopefully discipline about subsidies and agreeing on subsidy classification; improving monitoring of neutrality pledges, and more.

But even the agreements which do not have strong dedicated sustainability provisions may help countries in the transformation. Take for example Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership – RCEP. It is often labelled as not having much on sustainability. Even so it will help members through other clauses (ROOs, competition, e-commerce, investment etc) to diversify, become more regionally integrated and resilient. So, in evaluation potential of RTAs one must look beyond direct provisions.

Agreements that are especially worthy of mention are those that target specific set of issues (climate change, gender, indigenous peoples etc) or sectors (digital, services, e-commerce, investment). Not all of them are standard RTAs, as a number of these are discussed under the auspices of the WTO among subgroups of (like-minded) members. In the region, these efforts are often driven by small open economies such as New Zealand and Singapore but are seeking broader support. It is hoped that Sri Lanka will become more active in this regard.

I must not end without mentioning another worthwhile initiative of UN agencies, academia and supported by trade practitioners (aka negotiators). This initiative was started early in the pandemic to improve design of RTAs so they could be used as a guide (lighthouse if you wish) when crises hit and when ordinary trade rules do not provide much lead. Please see more details by visiting Model provisions for trade in times of crises in RTAs.

2. Are you seeing domestic policy shifts in sustainable trade? What countries are leading this change in Asia? And are these policy shifts specific to certain sectors?

Here are many country shifts worth mentioning but also, it would be useful to call out those governments which are not making much progress. The report I mentioned documents these changes in different areas. Let me start with New Zealand – as my chosen homeland – I am proud that New Zealand continues to be the vanguard of trade policymaking. In fact, one important reason I decided to settle in New Zealand more than 3 decades ago was the sweeping trade reforms the country braved to implement in the mid-1980s. It was a rare experiment in trade liberalization. Since then, New Zealand came to learn that being the most efficient producer is not a guarantee for high wellbeing for all in a country. Thus, its trade and investment policies, but also fiscal, health, monetary etc., policies got more aligned towards sustainable trade and sustainable development.

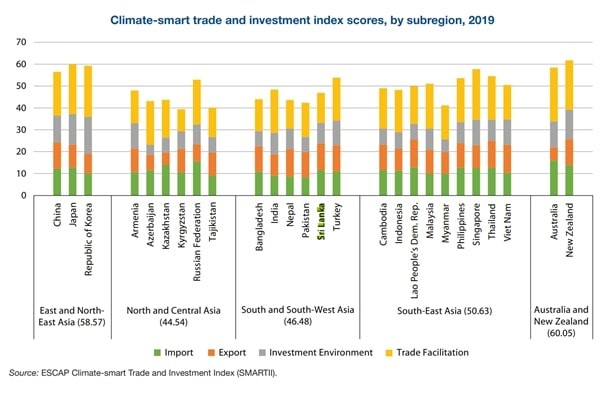

There are indices that monitor countries’ performance in a pursuit of sustainable development. Let me mention two. The climate-smart trade and investment index shows that countries in Asia-Pacific are making progress since 2015 but there is still much scope for improvement, especially in South Asia. Another dataset, the Sustainable Trade Index tracks 20 countries across economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainability. According to the 2020 report, Sri Lanka was doing well (just a bit above average) on environment but was lagging on economics and in particular social front.

In addition to these overall scores, let me mention some countries in terms of specific achievements:

- In terms of aligning tariffs, Bangladesh, Nepal and Azerbaijan are the only developing economies which have lower tariffs on clean green items as compared to carbon intensive fuels. Average environmental goods tariff for Sri Lanka is 8% while 7% is charged on carbon intensive fuels.

- In terms of use of Non-Tariff Measures to promote climate-smart trade, we have:

- Australia requiring application of fuel consumption labels and energy consumption labels to vehicles.

- China with technical requirement regarding the minimum allowable level of energy efficiency of self -ballasted fluorescent lamps has been specified.

- Brunei Darussalam prohibiting felling certain tree to slow down and control deforestation.

- New Zealand applying the levy to a range of imported goods including fridges, freezers, heat pumps, air-conditioners, and refrigerated trailers. It is linked to the price of carbon and varies between items to reflect the amount of gas, the specified gas and its global warming potential.

- Afghanistan banning imports of Chloro Floro Carbons (CFS) and products containing CFS and certain halons and products containing them.

There are other examples worthy of mention, but I must ask readers to review the report.

3. In your view, how has the pandemic influenced the adoption of sustainable trade policies in the region? And what is the role of sustainable trade in post-COVID 19 economic recovery?

The pandemic played enormously significant role in the region as it allowed everyone to open to opportunities that crisis created (mostly but not exclusively by making use of digital technologies). I am n ot saying that we should or can see pandemic only as a positive force – it cannot ever be painted as that because of irreplaceable lives (human capital) we lost.

What I want to say is this: when one is on the ground, the only way to move forward is to get up and start walking. But it is also smart to find out why one tripped and fell so that it can be prevented in the future. So, we need to look at the pandemic as giving us that opportunity- to reflect, rethink, restructure / reconfigure how to move on; to “build forward better.” That does not mean that everything must be changed, not at all, but it gives us opportunity to get rid of the things that we or we felt were not right but were afraid to change because of various costs involved (companies were afraid of loosing step with competition; governments of losing votes; individuals of not finding new jobs, etc). Sectoral disruptions, extraordinary fast uptake of digitalization, and changes in labour market opened so may new possibilities. Number of governments adopting or thin king about introducing “Trade for all” strategies is still low, but it is growing, and we should make sure this momentum is maintained.

There are many risks ahead of us (in near term we are still facing supply chain issues; in a medium to long term, we are looking at inflation, expensive money, and a return of stagflation?). What I see as a major risk is transferring what is happening in the current response to Omicron- its normalization and acceptance of “living with COVID” - to us starting to normalize “living with climate change.” This might reduce efforts to act and change behaviour which is needed to take us to sustainable trade and development. This is a real threat.

Annex: